Our Stories in Stained Glass

Dedicated in 1962, Saint Ann Church, like our Catholic faith, incorporates both ancient and contemporary forms of art and worship. We celebrate Eucharist at the altar, a table that reminds us of Christ’s Holy Thursday meal. The celebrant consecrates the bread and wine with words from Saint Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians (11:23-25), the earliest written account of the institution of the Lord’s Supper in the New Testament. The stained glass windows that surround us as we offer praise and thanksgiving to God represent a major art form that arose during the Middle Ages. The windows fill the church with light and color. They also tell us stories.

Members of the Stewardship Council did some research in preparation for our popular summer tour of the church and discovered stories in the glass and stories about them, too.

The windows were made in 1962 by the Hiemer & Company Stained Glass Studio in Clifton, NJ. Renowned liturgical artist Jacob Renner, who had emigrated from Munich in the 1920’s, created the designs in ink and water color. Simon Berasaluce, from the Basque country of Spain, did the painting on the glass. Saint Ann’s pastor, Rev. Francis Breen, was an active participant in the process, suggesting more contemporary touches in background and border. The resulting style, according to the Hiemer Company, is “a very successful marriage of the old and new,” a nice complement to the architecture of the church.

The towering choir loft window, seen most clearly from the sanctuary, might be called the Passion Window. Many of the panels focus on the objects and symbols of Christ’s suffering and death.

Within a laurel wreath are the letters SPQR, an abbreviation for the Latin Senatus Populusque Romanus (The Senate and the People of Rome), symbolic of Ancient Rome and the civil authority that presided over Jesus’ trial. The column with cords and whips represents the pillar where Jesus was scourged while the dice and tunic from another panel are from John’s account of the Passion (19:23-24) where the soldiers cast lots for Jesus’ tunic.

The Roman soldiers who arrested Jesus carried swords and lanterns. Peter, anxious to defend his Master, drew a sword and cut off the ear of Malchus, the high priest’s servant. According to tradition, Veronica pitied Christ and wiped the blood from his face as he made

The Roman soldiers who arrested Jesus carried swords and lanterns. Peter, anxious to defend his Master, drew a sword and cut off the ear of Malchus, the high priest’s servant. According to tradition, Veronica pitied Christ and wiped the blood from his face as he made his way to Calvary. The imprint of his face and the crown of thorns remained on the cloth, called the vernicle after Veronica. This relic has been preserved at Saint Peter’s in Rome since the eighth century. The cross of Christ is seen with Pilate’s

his way to Calvary. The imprint of his face and the crown of thorns remained on the cloth, called the vernicle after Veronica. This relic has been preserved at Saint Peter’s in Rome since the eighth century. The cross of Christ is seen with Pilate’s  inscription. INRI stands for Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews; in Latin, where I stands for J, Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum. The hammer and pincers were tools for the

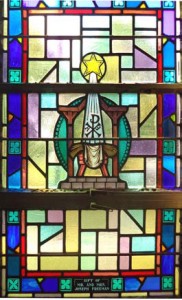

inscription. INRI stands for Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews; in Latin, where I stands for J, Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum. The hammer and pincers were tools for the  crucifixion and the removal of the body. The ladder, too, was used to remove Christ’s body from the cross, while the spear represents the one the Roman soldier used to pierce Jesus’ side. The INRI cross gives way to the draped cross (see photo at the bottom of this article), emblazoned now with the Chi Rho (PX), a symbol derived from the Greek word for Christ. The cross is draped with the winding cloth used for his burial, left behind now that Jesus has risen from the dead.

crucifixion and the removal of the body. The ladder, too, was used to remove Christ’s body from the cross, while the spear represents the one the Roman soldier used to pierce Jesus’ side. The INRI cross gives way to the draped cross (see photo at the bottom of this article), emblazoned now with the Chi Rho (PX), a symbol derived from the Greek word for Christ. The cross is draped with the winding cloth used for his burial, left behind now that Jesus has risen from the dead.

The Church’s “Hidden” Windows

Part of the exceptional beauty of Saint Ann Church stems from the design and placement of its stained glass windows. Many of them provide subtle variations on the “form follows function” axiom of architecture, especially the “hidden” windows in the two shrines and in the Reconciliation Room. When it was designed and built in the early  1960’s, prior to Vatican II, the church had confessionals in the side aisles where today we have the shrines. Behind the priest’s chair in each confessional was a window of striking significance for the Sacrament of Penance. In one, the current Shrine to Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the window includes a cross-anchor, an anchor whose upper beam forms a cross. An early Christian symbol for the cross, the anchor symbolizes the hope of salvation and eternal life. The scales, suspended from the cross, are symbols of justice and judgment, used for weighing good and evil, right and wrong. Atop the crossanchor is the chi-rho (PX), a symbol derived from the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ. The window in the Psalm Book Shrine depicts crisscrossed keys,

1960’s, prior to Vatican II, the church had confessionals in the side aisles where today we have the shrines. Behind the priest’s chair in each confessional was a window of striking significance for the Sacrament of Penance. In one, the current Shrine to Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the window includes a cross-anchor, an anchor whose upper beam forms a cross. An early Christian symbol for the cross, the anchor symbolizes the hope of salvation and eternal life. The scales, suspended from the cross, are symbols of justice and judgment, used for weighing good and evil, right and wrong. Atop the crossanchor is the chi-rho (PX), a symbol derived from the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ. The window in the Psalm Book Shrine depicts crisscrossed keys,  which signify the power Peter received from Jesus to forgive sins: “I will give you the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in Heaven and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in Heaven.” (Matt 16:19). One key is silver, representing the earth. The other is gold, for heaven. The purple stole is also meaningful. The stole is a symbol of the ordained priesthood while purple is the color for repentance and sorrow. The priest wears a purple stole during the Sacrament of Reconciliation. In the original design of the church the baptismal font was located in the vestibule, in

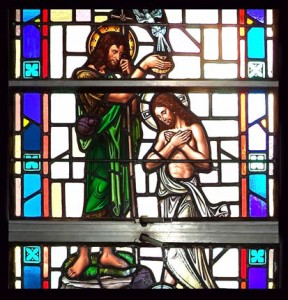

which signify the power Peter received from Jesus to forgive sins: “I will give you the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in Heaven and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in Heaven.” (Matt 16:19). One key is silver, representing the earth. The other is gold, for heaven. The purple stole is also meaningful. The stole is a symbol of the ordained priesthood while purple is the color for repentance and sorrow. The priest wears a purple stole during the Sacrament of Reconciliation. In the original design of the church the baptismal font was located in the vestibule, in  full view of the window that depicts the Baptism of Jesus. That window is now “hidden” in the Reconciliation Room. The gospels tell us that when John had baptized Jesus at the River Jordan the heavens opened and “he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove.” (Matt 3:16) The window includes the dove, with halo and rays of light, representing the Holy Spirit. Christ is depicted with a cruciform halo, one with a cross inscribed, a traditional symbol of Jesus. As is typical in Christian art, John pours the baptismal water from a scallop shell, which has become a symbol of Baptism. The window was a gift from the children of Saint Ann Parish – how appropriate!

full view of the window that depicts the Baptism of Jesus. That window is now “hidden” in the Reconciliation Room. The gospels tell us that when John had baptized Jesus at the River Jordan the heavens opened and “he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove.” (Matt 3:16) The window includes the dove, with halo and rays of light, representing the Holy Spirit. Christ is depicted with a cruciform halo, one with a cross inscribed, a traditional symbol of Jesus. As is typical in Christian art, John pours the baptismal water from a scallop shell, which has become a symbol of Baptism. The window was a gift from the children of Saint Ann Parish – how appropriate!

The Saint Ann Windows

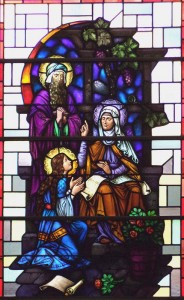

Saint Ann, our patroness, is depicted in two of the beautiful stained glass windows on the Psalm Shrine side of the  church. Most of what we know about the mother of the Virgin Mary, even her name, comes from the Protevangelium of James, a second century gospel that is not included in the canon of Scripture. We see Saint Ann as teacher in the window at left, imparting wisdom and knowledge to the attentive young Mary as Saint Joachim, Ann’s husband and Mary’s father, stands prayerfully behind them. Devoted parents, long childless, Ann and Joachim are training their daughter in the religious traditions of her people. She, in turn, will train her son in those traditions. Mary is dressed in blue, the “color of an empress” according to Father Johann Roten, an internationally recognized scholar and

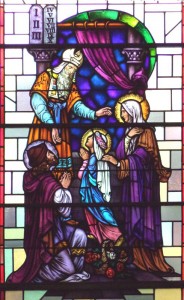

church. Most of what we know about the mother of the Virgin Mary, even her name, comes from the Protevangelium of James, a second century gospel that is not included in the canon of Scripture. We see Saint Ann as teacher in the window at left, imparting wisdom and knowledge to the attentive young Mary as Saint Joachim, Ann’s husband and Mary’s father, stands prayerfully behind them. Devoted parents, long childless, Ann and Joachim are training their daughter in the religious traditions of her people. She, in turn, will train her son in those traditions. Mary is dressed in blue, the “color of an empress” according to Father Johann Roten, an internationally recognized scholar and  authority on Mary. Roses, long considered Mary’s flower, are scattered at her feet. The window at right shows Ann and Joachim presenting Mary in the temple, fulfilling their promise to dedicate their long-awaited child to the Lord. Mary wears a blue mantle. Her white veil is adorned with roses, which you can also see in a basket at her feet. Ancient tradition says that the high priest who received her was Zechariah, who would become the father of John the Baptist. Behind the high priest are the Ten Commandments. The first three, which treat our relationship with God, appear on one tablet while the last seven, concerning our relationship with one another, are on the second. Devotion to Saint Ann arose in the early Church, particularly in the East. Widespread devotion in the Western church began in the sixteenth century.

authority on Mary. Roses, long considered Mary’s flower, are scattered at her feet. The window at right shows Ann and Joachim presenting Mary in the temple, fulfilling their promise to dedicate their long-awaited child to the Lord. Mary wears a blue mantle. Her white veil is adorned with roses, which you can also see in a basket at her feet. Ancient tradition says that the high priest who received her was Zechariah, who would become the father of John the Baptist. Behind the high priest are the Ten Commandments. The first three, which treat our relationship with God, appear on one tablet while the last seven, concerning our relationship with one another, are on the second. Devotion to Saint Ann arose in the early Church, particularly in the East. Widespread devotion in the Western church began in the sixteenth century.

The Birth and Early Life of Jesus

Three of our beautiful stained glass windows tell the story of the

Three of our beautiful stained glass windows tell the story of the  Holy Family, Jesus, Mary and Joseph. The Nativity window at left could be a Christmas card. Here is the infant Jesus lying in a manger, a feeding trough for animals. His two raised fingers represent the two natures of Christ, divine and human. The star above, which led the Magi to Bethlehem, is in the form of a cross, a portent of what lies ahead. A prayerful Joseph stands near Mary, who is dressed in her traditional colors. Her tunic is red, the color of love and religious aspiration. Over the tunic is a mantle of blue, the color of constancy and heavenly purity. The workshop window at right presents a picture of Jesus’ early life and reinforces the importance of the family unit. Mary is the image of the worthy wife from the Book of Proverbs whose “fingers ply the spindle” while the young Jesus trains under the watchful eye of Joseph, his earthly

Holy Family, Jesus, Mary and Joseph. The Nativity window at left could be a Christmas card. Here is the infant Jesus lying in a manger, a feeding trough for animals. His two raised fingers represent the two natures of Christ, divine and human. The star above, which led the Magi to Bethlehem, is in the form of a cross, a portent of what lies ahead. A prayerful Joseph stands near Mary, who is dressed in her traditional colors. Her tunic is red, the color of love and religious aspiration. Over the tunic is a mantle of blue, the color of constancy and heavenly purity. The workshop window at right presents a picture of Jesus’ early life and reinforces the importance of the family unit. Mary is the image of the worthy wife from the Book of Proverbs whose “fingers ply the spindle” while the young Jesus trains under the watchful eye of Joseph, his earthly  father. The Greek word “tekton,” used to describe Jesus and Joseph in the New Testament, is a common term for an artisan/craftsman, especially a wood worker, builder or carpenter. The “Finding of Jesus in the Temple” window illustrates the story found in Luke’s gospel (2:41-52) and the fifth Joyful Mystery of the Rosary. Devout Jews, Mary and Joseph traveled to Jerusalem every year to celebrate the Passover. They made the 3-day, roughly 80 mile trip in a caravan with relatives and friends. On the return trip when Jesus was 12 years old his parents realized that he was not with them and went back to look for him. “After three days,,” Luke tells us, “they found him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions.” The teachers “were astounded” at the understanding and the answers of this precocious child. (Notice how the rabbis are looking up as they sit at the feet of Jesus. He has become the teacher.) To his mother’s anxious “why?” Jesus replied, “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?” For the first time Jesus indicates that he is the Son of God. His Father’s work, as later Gospel stories show, will take precedence over family ties. But Jesus returns to Nazareth with Joseph and Mary, is obedient to them and “advance[s] in wisdom and age” as he prepares for his ministry. In his depiction the artist has included both scrolls, representing the Old Testament, and a book, which represents the New Testament.

father. The Greek word “tekton,” used to describe Jesus and Joseph in the New Testament, is a common term for an artisan/craftsman, especially a wood worker, builder or carpenter. The “Finding of Jesus in the Temple” window illustrates the story found in Luke’s gospel (2:41-52) and the fifth Joyful Mystery of the Rosary. Devout Jews, Mary and Joseph traveled to Jerusalem every year to celebrate the Passover. They made the 3-day, roughly 80 mile trip in a caravan with relatives and friends. On the return trip when Jesus was 12 years old his parents realized that he was not with them and went back to look for him. “After three days,,” Luke tells us, “they found him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions.” The teachers “were astounded” at the understanding and the answers of this precocious child. (Notice how the rabbis are looking up as they sit at the feet of Jesus. He has become the teacher.) To his mother’s anxious “why?” Jesus replied, “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?” For the first time Jesus indicates that he is the Son of God. His Father’s work, as later Gospel stories show, will take precedence over family ties. But Jesus returns to Nazareth with Joseph and Mary, is obedient to them and “advance[s] in wisdom and age” as he prepares for his ministry. In his depiction the artist has included both scrolls, representing the Old Testament, and a book, which represents the New Testament.

The Evangelist Windows

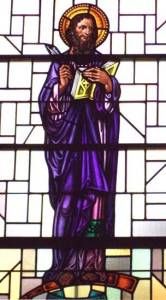

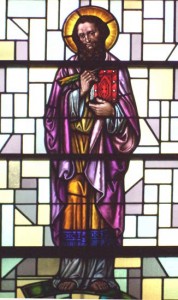

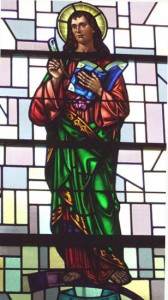

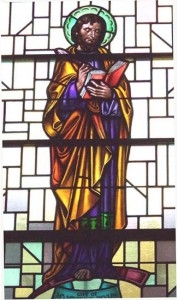

Nowhere in Saint Ann Church do art and architecture come together with greater significance than in the sanctuary. Here, in this consecrated space where we celebrate Mass, we see the altar, a symbol of the Liturgy of the Eucharist, and the Evangelist windows, eloquent symbols of the Liturgy of the Word. Taken together they represent the two different parts of the “one single act of worship” that is the Mass. Most of us are familiar with the names of the Evangelists, the four Gospel writers: Matthew, who was probably not the tax-collector apostle; Mark, who had traveled with both Paul and Peter; Luke, the Gentile who is said to have been a physician; and John, the youngest of the twelve apostles. And many of us probably thought we knew which stained glass evangelist was which. To be certain, however, we went to the source, the great folks at New Jersey’s Hiemer & Company, who supplied the windows in 1962.

Nowhere in Saint Ann Church do art and architecture come together with greater significance than in the sanctuary. Here, in this consecrated space where we celebrate Mass, we see the altar, a symbol of the Liturgy of the Eucharist, and the Evangelist windows, eloquent symbols of the Liturgy of the Word. Taken together they represent the two different parts of the “one single act of worship” that is the Mass. Most of us are familiar with the names of the Evangelists, the four Gospel writers: Matthew, who was probably not the tax-collector apostle; Mark, who had traveled with both Paul and Peter; Luke, the Gentile who is said to have been a physician; and John, the youngest of the twelve apostles. And many of us probably thought we knew which stained glass evangelist was which. To be certain, however, we went to the source, the great folks at New Jersey’s Hiemer & Company, who supplied the windows in 1962.

Matthew Mark Luke John

Christian art traditionally uses certain symbols for the Evangelists: ox (Matthew), lion (Mark), eagle (Luke), man (John). Our windows have no such symbols, nor do they have name plates! According to Hiemer’s files, the two figures above are Matthew and Mark, who seem older with “receding hair and perhaps a few more character lines, as is traditional in portraying the four as a set.” Luke is usually depicted as “a bit younger” than Matthew and Mark, and usually wears a gold or amber garment. John, “always the easiest to identify,” is “the unshaven apostle” who “stands out as the youngest and the one whom Christ loved.” That the four are Evangelists is “inherent in their poses with books and quill in hand, not historically accurate, of course, but again traditional symbols to indicate the fact that they wrote.” Judith Hiemer Van Wie, our gracious source of information, shared this observation: “Artistically you have beautifully developed figures with particularly excellent portraits. The wonderful rich color of the garments is offset by the rather light colored neutral background. This really makes the figures ‘pop.’ That richness is then contained by a border of equal intensity [which does not appear in the photos above but is clearly visible in the church]. The whole offers traditional stained glass that allows plenty of light into the church unlike the old medieval windows that used rich heavily painted colors throughout.”

Parish History Reflected in Stained Glass

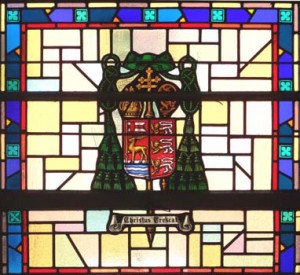

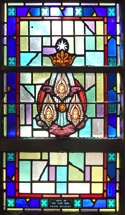

Two stained glass windows in the sacristy are colorful and artistic footnotes in parish history. Once it had become an independent parish Saint Ann’s purchased the land on the corner of Naugatuck Avenue and Church Street – our present campus – and built a basement church, which was dedicated in 1924. The present church, built on the basement church foundation, was dedicated in 1962. The windows depict the coats of arms of the recently canonized Saint John XXIII, Pope during the time the church was built, and the Most Reverend Henry J. O’Brien, Archbishop of Hartford during the time of the church’s construction. The tiara and key on John XXIII’s coat of arms, pictured at left, symbolize the papacy and the spiritual authority of the pope as the vicar of Christ on earth. John included the winged lion, the symbol of Saint Mark the Evangelist, to represent his association with Venice, where he had served as patriarch, and its magnificent Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark. The lion’s paw rests on tablets that proclaim, Pax tibi Marce evangelista meus (Peace to you, Mark, my evangelist). The two fleurs-de-lis signify the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph, while the stone tower represents God, a tower of refuge, and the linking of heaven and earth.

Two stained glass windows in the sacristy are colorful and artistic footnotes in parish history. Once it had become an independent parish Saint Ann’s purchased the land on the corner of Naugatuck Avenue and Church Street – our present campus – and built a basement church, which was dedicated in 1924. The present church, built on the basement church foundation, was dedicated in 1962. The windows depict the coats of arms of the recently canonized Saint John XXIII, Pope during the time the church was built, and the Most Reverend Henry J. O’Brien, Archbishop of Hartford during the time of the church’s construction. The tiara and key on John XXIII’s coat of arms, pictured at left, symbolize the papacy and the spiritual authority of the pope as the vicar of Christ on earth. John included the winged lion, the symbol of Saint Mark the Evangelist, to represent his association with Venice, where he had served as patriarch, and its magnificent Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark. The lion’s paw rests on tablets that proclaim, Pax tibi Marce evangelista meus (Peace to you, Mark, my evangelist). The two fleurs-de-lis signify the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph, while the stone tower represents God, a tower of refuge, and the linking of heaven and earth.

Archbishop O’Brien’s coat of arms, at right, features three lions from the O’Brien family crest. The lion is also considered a symbol of the resurrection. By tradition the arms of the Archbishop are joined to the arms of his diocese, seen on the left side of the shield. Here, on a field of red, is a golden hart (stag) crossing a ford. The hart bears the golden staff of a Paschal banner in red and white, a symbol of Jesus Christ. The blue and silver wavy lines represent the waters of the Connecticut River, which flows through the Nutmeg State. The hart is also considered a symbol of the faithful Christian’s longing for God. These coats of arms, created in colorful stained glass at Saint Ann’s, are also incorporated into the great Bronze doors of the Cathedral of Saint Joseph in Hartford, sculpted by Enzo Assenza. John XXIII’s papal coat of arms can be seen as the top panel of the West doors, while Archbishop O’Brien’s coat of arms appears on the East doors top panel. The cathedral, a modern Gothic and Byzantine building emerged from the ashes of Hartford’s original brownstone cathedral which was destroyed in a tragic fire in 1956. The rebuilt cathedral, like Saint Ann’s, was dedicated in 1962.

The Children’s Chapel Windows

The room we call the Children’s Chapel had a different name when Saint Ann Church was dedicated in 1962. It was called the Mothers’ Room, a place designed for moms and their little ones. During Mass they could see into the sanctuary through the large double window. They could hear the prayers, the readings and the homily, but they could not be heard. Only Mom (and Dad if he was there) heard the fussy baby or the inquisitive or complaining toddler. (After several years, in fact, the space was known as the Cry Room prior to its modern-day upgrade to Children’s Chapel.)

The room we call the Children’s Chapel had a different name when Saint Ann Church was dedicated in 1962. It was called the Mothers’ Room, a place designed for moms and their little ones. During Mass they could see into the sanctuary through the large double window. They could hear the prayers, the readings and the homily, but they could not be heard. Only Mom (and Dad if he was there) heard the fussy baby or the inquisitive or complaining toddler. (After several years, in fact, the space was known as the Cry Room prior to its modern-day upgrade to Children’s Chapel.)

The original name takes on great significance when we look at the four stained glass windows that adorn the space. According to Heimer & Company, the stained glass studio in New Jersey that made them, the windows depict symbols of our Blessed Mother taken from the Litany of Loreto.

Approved by Pope Sixtus V in 1587 the Litany includes various titles for Mary. One of them, Our Lady of Loreto,  refers to the Holy House of Loreto which, according to legend, is the house where the Holy Family lived in Nazareth. It is said that during the Crusades, when it was threatened with destruction by the Saracens, the Holy House was brought first to Tersato, Dalmatia in 1291, then to Recanati, Italy in 1294 and finally to Loreto, Italy where a basilica was built around it. (Legends vary. Some say Crusaders transported the Holy House. According to others a band of angels carried it aloft. ) The Shrine of Loreto, long a destination for pilgrims, is under the direct authority and protection of the Pope. Countless miracles attributed to Our Lady have been recorded there.

refers to the Holy House of Loreto which, according to legend, is the house where the Holy Family lived in Nazareth. It is said that during the Crusades, when it was threatened with destruction by the Saracens, the Holy House was brought first to Tersato, Dalmatia in 1291, then to Recanati, Italy in 1294 and finally to Loreto, Italy where a basilica was built around it. (Legends vary. Some say Crusaders transported the Holy House. According to others a band of angels carried it aloft. ) The Shrine of Loreto, long a destination for pilgrims, is under the direct authority and protection of the Pope. Countless miracles attributed to Our Lady have been recorded there.

The Three Faces window (top left) illustrates Mary’s title Queen of Angels. The crown denotes royalty and here the winged faces represent celestial beings. The star further suggests “the heavens,” wherein the angels abide.

The Nativity window (top right) depicts the title Mother of Christ. The P and the X, the first two letters in the name of Christ in Greek characters, form the Chi Rho, a symbol for Christ. In this window the artist has included within the symbol the Alpha and Omega, affirming the divinity of Christ, the beginning and end of all. The Alpha and Omega may stand alone in liturgical art to identify Christ.

The Dove (above, left) is Queen of Peace, denoted by the crown above and the olive branch in the dove’s mouth. Without a halo a dove represents peace in Christian art. With a halo, especially one with a cruciform, or inscribed cross, within it, the dove represents the Holy Spirit.

The beautiful Rose window illustrates Mary as Mystical Rose. The Chi Rho’s P and the branches of the X peek out around the central rose.

During the Middle Ages, when stained glass developed as a major art form, especially in Gothic style churches, the windows filled the church interiors with light and color. Few people could read and so the windows were also an educational tool, telling stories from Scripture. Centuries later our windows, too, tell stories. In the Mothers’ Room we learn more about Mary, our mother, the daughter of our patroness, the Mother of Our Lord.

At right, from the Passion window, the cross emblazoned with the Chi Rho ( PX), The cross is draped with the winding cloth used for Christ’s burial, left behind now that Jesus has risen from the dead.